On Tuesday, 13th April, 1999, John Lippmann, the late, Bob Ramsay, Grahame Weir and myself settled down in the former Billiard Room at Raffles Hotel, Singapore, for a quiet little drink as a prelude to the start of the following day’s Diving Conference (organised by DEMA) that would precede the opening of that year’s ADEX Show.

On Tuesday, 13th April, 1999, John Lippmann, the late, Bob Ramsay, Grahame Weir and myself settled down in the former Billiard Room at Raffles Hotel, Singapore, for a quiet little drink as a prelude to the start of the following day’s Diving Conference (organised by DEMA) that would precede the opening of that year’s ADEX Show.

Following a drink or two, we began – as divers often do? – to tell stories of our disasters rather than of our undoubted bravery and courage. John Lippmann was so impressed by some of the tales of derring-do that he insisted on picking up the tab. Bob recalls John’s face going white when he was presented with the bill.

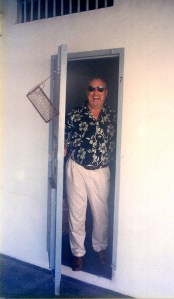

John was still suffering the next morning when, at Bob’s invitation, we visited the Singapore Naval base – formerly, HMS Terror, at Sembawang, in the north of the island – where (at what used to be the main gate cell block) I was able to re-live some of my more ‘memorable’ moments. One of which – the image and the story – follows:

————-

Harking back to 1969 while on board HMS Albion.

Shortly before leaving Singapore and sailing for home, I joined three R.O. (Radio Operator) friends for a quiet afternoon ashore. Winding up at a bar called the, ‘Crown and Anchor’, a short distance from Sembawang village, on the road to Nee Soon, we decided to work our way through their extensive list of overseas beers. Faced with a variety of exotic labels, I decided to save them as ‘collectables’. Unwilling to fold or crease these paper gems that I’d carefully peeled from each consumed bottle, and no obvious place to keep them (my shore-going attire was a pair of trousers and a polo shirt) I hit on the idea of sticking them across my chest and stomach.

We left the bar in the early evening and, having decided to return to Sembawang, discussed the merits of a taxi, or whether to save the money and walk. Three of us were in favour of walking, while one held out for the taxi option. The two in favour of walking set off up the road towards Sembawang, alongside of which was a deep monsoon ditch. I followed. The fourth member of our little band traipsed along behind, miffed that nobody would agree to share the cost of a taxi with him, and emphasising his complaints by continually prodding me in the back.

Eventually responding to his annoying pokes and prods I turned around and gave him a shove. He pushed back. I punched him. He punched back, and the scuffle began. Sadly, neither of us had allowed for our proximity to the monsoon ditch. We fell in, still fighting and rolling around in the damp dirt.

At this point, I should explain that it was common practice when a number of ships of allied nationalities were in port, for the Naval Shore Patrols to be made up of a representative mix. Not only did this save on manpower, it also avoided any later arguments about jurisdiction from ‘lower deck lawyers’. Unbeknownst to us, our weaving progress had been observed by a shore patrol stationed in a ‘Paddy-Wagon’ parked close to the bar. Led by a Leading Regulator from the shore base at HMS Terror, the uniformed patrol included a Brit, an American, an Australian, and a New Zealander.

Suddenly made aware that our brawl had been illuminated by the light from four powerful torches, we were ordered out of the ditch. Joining forces against what we perceived as the common enemy, we told them to go away and leave us to our discussions. An unwise decision brought home to us by the American patrolman who threatened to use his nightstick on both of our heads unless we complied. Listening to the voice of reason, we climbed out of the ditch, produced our Identity Cards as requested and were ushered into the ‘prisoner-transport’ back of the wagon for the trip back to the guardhouse standing at the entrance to HMS Terror.

Ushered into the guardroom and paraded in front of the duty Petty Officer, the charges against us – that of fighting ashore – were read out. Having been first of all told that we’d spend the night in cells as prisoners before, on the following morning, being returned to the ship to face whatever punishment the skipper deemed suitable, the duty medical officer was then summoned to check us out for life-threatening injuries.

Ushered into the guardroom and paraded in front of the duty Petty Officer, the charges against us – that of fighting ashore – were read out. Having been first of all told that we’d spend the night in cells as prisoners before, on the following morning, being returned to the ship to face whatever punishment the skipper deemed suitable, the duty medical officer was then summoned to check us out for life-threatening injuries.

Arriving at the guardhouse a short while later, the uniformed medical officer checked out my mate before turning his attention to me. Examining my head and jaw for obvious injuries, he then ordered me to lift up my shirt to check for broken ribs. Having forgotten about my beer label ‘collectables’, I lifted my shirt. ‘This man”, declared the medical officer after viewing my collection, “is drunk.” After which, he retrieved his cap and slowly weaved his way back to the wardroom and duty-free pink gins.

Escorted into the cell block, I was ordered to hand over all of my possessions and strip down to my boxer shorts. I complied. After which I was shown into one of the cells, a narrow, concrete-floored room about four-metres deep by about two-metres wide containing nothing other than a single raised wooden platform screwed into concrete plinths. At one end, a fixed wooden ‘pillow’ on this make-shift bed faced a grilled light. Across the gap between the sloping tiled roof and the cell’s high walls lay a screen of steel mesh. The single narrow and outward opening door featured a barred grille at face level, and was held closed by three barrel-bolts; one at the top; one mid-way down, and the third lower still.

At this point my beer befuddled brain took control. I announced that I couldn’t be locked up because I suffered from claustrophobia. (I didn’t, but they weren’t to know that.) Ignoring my comments, the door was slammed shut and the bolts pushed home.

Feeling aggrieved, I launched a feet-first attack on the barrier to freedom. My efforts started to pay dividends when the top bolt fitting parted company with the door frame. Based on the fact that the door was only wide enough for one person at a time to enter the cell, and convinced that the odds were in my favour, I disregarded the threats to come in and physically restrain me.

Fuel ed by beer and adrenalin, my assault on the door continued. The remaining two bolts gave way in quick succession. The door flew open, and what I’d mentally planned as, ‘The Great Escape’ into Singapore – albeit dressed only in my boxer shorts – was foiled by the semi-circle of baton wielding guards advancing on me. Like perfectly trained sheep dogs, they herded me into an empty cell next to the one that I’d just escaped from. Drained of energy and enthusiasm for another escape attempt, I collapsed on the bed and slept through to morning when, reunited with my clothes and possessions, I was returned to the Albion and handed over to the Master-At-Arms.

(A Master-At-Arms is a senior rating charged with enforcing discipline aboard ships. Apart from officers, they are the only members of a ship’s company permitted to wear a sword on ceremonial occasions and are addressed as, “Master”.)

As a ‘defaulter’ I was ordered to appear at the Captain’s Table where, defended by my Divisional Officer, Naval justice would be dispensed and enforced. Marched in and ordered – as a wrong-doer – to remove my cap, the charge against me of being drunk and fighting ashore was read out by the Master-At-Arms. Addressing my Divisional Officer (D.O.) the Captain asked how I pleaded? “He pleads guilty, Sir.”. The sentence was passed; stoppage of leave, stoppage of pay, and additional duties.

A few days into my sentence, I received an order to report to the Master-At-Arms who announced that he had just received a supplementary report from the Regulating Office at HMS Terror. The additional charge was causing damage to Her Majesty’s property – to whit, one cell door – and that I would be appearing in front of the Captain’s Table to face the additional charges … and accompanying punishment.

Feeling somewhat put upon – and very aware that even the lowest rating has the right to appeal any punishments handed down – I explained that the damage had only been caused because nobody had accepted my claim that I suffered from claustrophobia and the refusal to again have the duty medical officer return to the guardroom. Asked by the Master-At-Arms whether or not, I did, in fact, suffer from claustrophobia, I confessed to the lie. “But,” I said, “they weren’t to know that. And if anyone’s to be punished, it should be those on duty at the Guardroom.” He thought for a while, and then told me to plead guilty. I said that I’d rather not. He ordered me to plead guilty and that he would ensure that the matter was resolved to everyone’s satisfaction.

Again appearing as a ‘defaulter’ in front of the Captain, the charge was read out; the Captain asked my D.O. how I pleaded? It was agreed by everyone that I was guilty, and that I should be fined two shillings and eight-pence half-penny for a packet of rawl-plugs to fix the cell door’s barrel bolts. The Master-At-Arms paid the money.

—ENDS—

Categories: General